What if there's no tomorrow

A short story about a Jewish captain of America and plenty o' cat pix

Hello and hello, good friends. Well, looks like we made it 20 years past Y2K. I count that as a victory. I’m back in Brooklyn after my Florida retreat and have been wasting a lot of time playing video games and thinking about the future. The world is very bad right now and I’m trying to ponder what a good thing could look like. A lot of that thought process ended up manifesting itself in a short story that I have included as this week’s Main Course. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. I’m heading to a New Year’s Eve party with my beloved and some dear friends in a few hours and have to get some glasses before that because my vision plan is use-it-or-lose-it, but I figure I can sneak a quick email in before then. Shall we?

Cat update

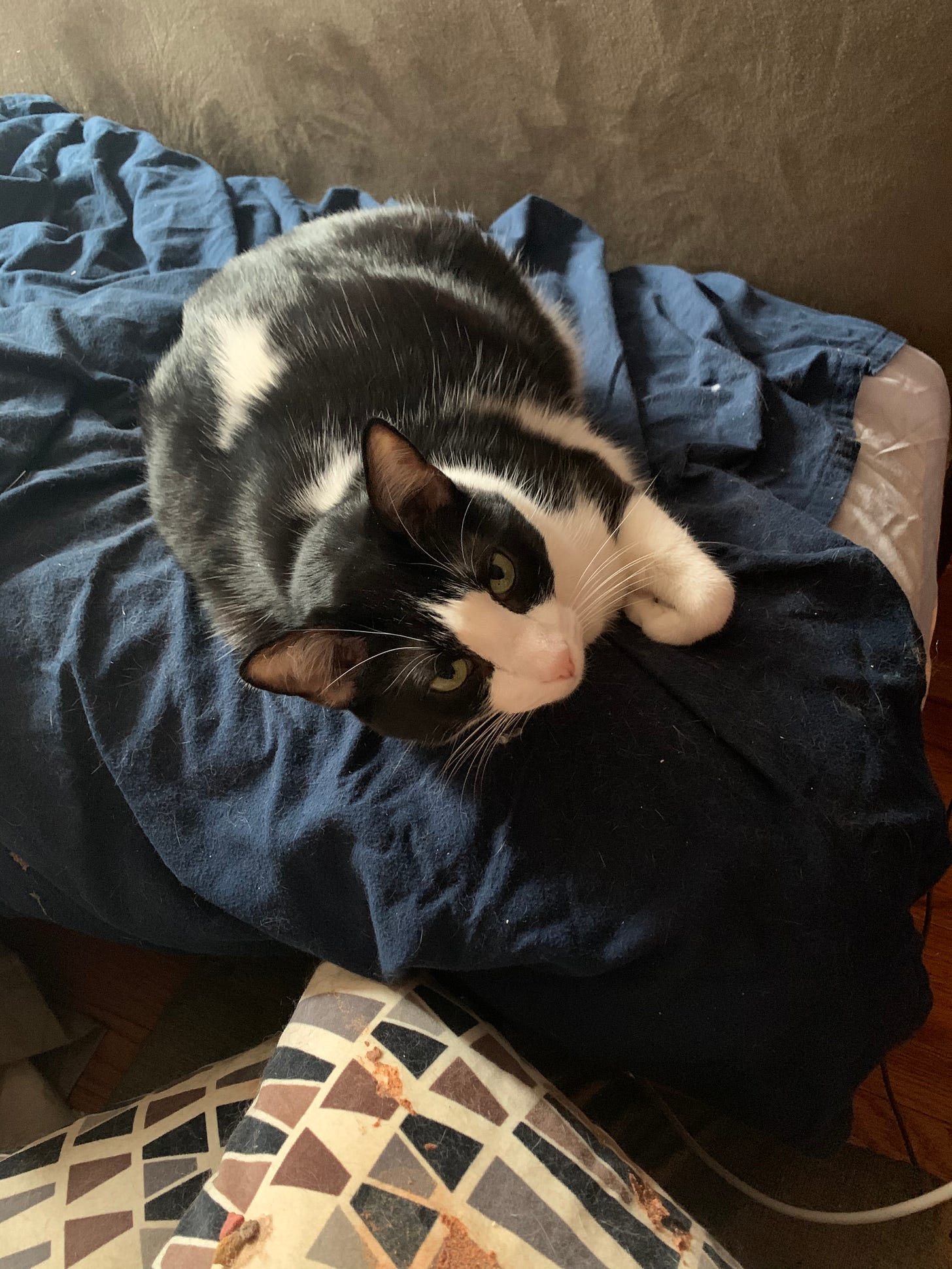

Cats are doing just fine. They were thoroughly unimpressed with my return to the apartment, which is the curse part of having two cats — they entertain each other, so you’re not as important. Here is Tim on the sheets I still haven’t taken off after my sister slept on them three nights ago:

And here is the divine rump of Ms. Barb:

Perusal

Wolf — As in, the Jack Nicholson movie. I watched it for the first time, at the urging of my partner, and was immediately seduced by it. They don’t make weird, mid-budget comedy-thrillers with A-list names like this one anymore. And oh my God, Michelle Pfeiffer is a vision.

Jedi: Fallen Order — I’m not much of a gamer, but, feeling bereft due to the awfulness of the new Star Wars movie, I decided to take a swing at the PS4 version of the latest game set in that venerable mythos. It’s really good! I’m nowhere near done with it because I’m bad at video games, but it packs an aesthetic wallop and the core concept — you play a Marrano Jedi trying to stay one step ahead of the Inquisition — is just compelling enough to rope you in. Here’s hoping I don’t get too bored to finish it!

Lift Your Skinny Fists Like Antennas to Heaven, Godspeed You! Black Emperor — I’ve long adored this album, but after a very intense conversation about God and religion with my boo, it occurred to me that the album kind of expresses all my thoughts on those subjects. I hope that’s not too pretentious to say!

Rokhl Kafrissen on anti-Zionism and neo-Bundism — Rokhl is an extremely smart person who can run circles around virtually anyone else’s knowledge of Eastern European Jewry and Yiddishkeit, and although I don’t 100% agree with her conclusions here, she makes a lot of necessary points.

Me, me, me

No new published work from yours truly since the last newsletter went out, sad to say. So I’ll instead jump into the archives and produce something a little embarrassing. On New Year’s Eve of 2009, for no particular reason, I published a ranking of the output of the Mountain Goats in the ’00s. I think it holds up! Here’s the link to read it on my terrible old blog.

Main course (be gentle, I don’t usually do this sort of thing)

A song of ascents. A sickly infant is born in Vienna’s Rothschild Hospital on the seventh day of the month of Cheshvan in the year 5646. The date recorded on his birth certificate is 16 October, 1885. His parents, Jews of Byelorusian extraction, made their way to Austria after the pogroms of four years prior. They are now secular, having abandoned the religion of their forebears out of fear as they left the burning remains of the village from which they came. A hospital rabbi offers to pray for the prematurely withered child during the reading of the week’s Torah portion. The parents politely refuse, but the mother asks what the portion is. The rabbi tells them it’s Lech Lecha. Without speaking, the parents both remember the words with which it begins: Vayomer Adonai el Avram lech lecha m’artzcha umimoladtecha umibeyt avicha el ha’aretz asher arecha. Without speaking, they both know they will name the boy Avram. Without speaking, they both know he will not die in the place of his birth.

They and everyone else call him Bram. His parents manage to build a stable, middle-class life for their quiet, spindly son. Bram’s compassionate father, once a devoted student of Talmud on the path to becoming his village’s gabbai, uses his aptitude for study to become a schoolteacher of mathematics. He lovingly drills the laws of the universe into his son from an early age. How can it be that all these laws simply are, Bram wonders, and who is it that devised them? but he feels such questions are stupid and so never utters them. Bram’s reserved mother, an autodidactic housewife with a passion for stories, reads great literature (though not the Bible) to the boy before bed, never explaining the material or cleaning it up. Why do such terrible things happen to the good people in the stories? Bram wonders, but doesn’t want to sound like a fool and so never speaks up. Bram never tells his parents, but he is terrified all the time about the world and its people.

When Bram is 12, a new mayor is elected in Vienna. He says terrible things about the Jews. Bram knows he is a Jew in some vague sense, but his parents never talk about their pasts and he cannot say what a Jew is, really, or what makes a Jew worthy of scorn. One day, a boy at Bram’s school kicks him in the shins, spits at him, and calls him kike. Bram does not know what the word means and so asks his parents that night. They turn as white as milk. His mother opens her mouth to tell him the origins and etymology of the word, but her husband, uncharacteristically, cuts her off and simply says to his only son, It is a word beyond reason, and you must be a child of reason. His mother nods and adds, Whatever that word is, you are not it. Bram lies awake in his bed that night, rolling these ideas over in his overheating mind.

Bram becomes obsessed with chemistry. He likes the idea that one entity can touch another entity and become a third entity. He likes the idea that chemical interactions are a kind of radical change. He is thinking a lot about radical change. The clouds are darkening in Europe — war in the Balkans, threats from the Kaiser, imperious idiocy among the British — and Bram becomes convinced that civilization is teetering on the brink of the abyss. He despairs at the fact that he cannot yet save the world. He thinks if he learns enough, if he knows enough about the world, perhaps he can save it. He devotes himself to his studies in a flurry of desire and anguish. He excels.

Bram does not take a wife and maintains an air of one who is too obsessed with his studies to have time for romance, but in reality maintains a series of deeply covert relationships with men. At age 21, he falls profoundly in love for the first time with the first man who ever penetrates him, a 23-year-old ethnic Croat refugee named Nikola who reads Bram poetry in tongues he never understands but loves to hear, nonetheless. Nikola dies in a carriage accident on Lerchenfelder Strasse and Bram cannot leave his bed for a week, telling friends he caught a mild case of influenza. He still takes lovers but does not truly love again for seven years, when he is pursuing his Ph.D in Salzburg and encounters an undergraduate student of his, an ethnic Magyar from Budapest named Lajos. Lajos is a fierce patriot of the Dual Monarchy, is exceptionally gifted at oral sex, and is too wild to remain exclusive but nevertheless loves Bram with all his heart. The feeling is mutual.

The Great War comes and two things occur in Bram’s life. First, Lajos is drafted, sent to war, and dies in his first day on the battlefield. A week after learning this news through mutual friends, Bram is informed that he has been selected by the Empire to devote his energies to military research. In a haze of grief and horror, he develops weapons, things that curdle the lung and inflate the eye. He has no real choice in this, yet with every passing day, he feels another molecule of his soul disappear. He starts to cut his left shoulder with a razorblade every once in a while, never quite sure whether he’s punishing himself or grasping at control over his misery.

The war ends and there is, for a time, something resembling optimism, or at least a theory that humanity’s fever has perhaps broken and the healing can begin. After obtaining his degree and publishing a paper on the effect of stomach acid on the bloodstream, Bram moves back to Vienna to take a job at a laboratory and care for his aging parents. His father dies of cancer and, in his dying breaths, whispers the Shema in Hebrew, although Bram is in the bathroom when this happens and wouldn’t have understood the words, anyway. His mother moves in with him, which puts a dent in his casual liaisons, but he feels a sense of duty to her. For the first few years, she mostly sits in her chair and reads, but when her eyes start to fail her, Bram reverses the roles from his childhood and reads literature aloud to her. Occasionally, he asks if she’d like to hear the newspaper, but she always says no. Bram thinks this is probably for the best, as there is no good news anymore.

It becomes increasingly difficult for Bram to wend his way through the world, given his ethnic background. Eskin isn’t a common Jewish surname and Bram doesn’t look like the hooknosed caricatures in the pamphlets the antisemites hand out on the street, so he’s often able to blend in. But occasionally, a colleague will learn through the grapevine that Bram is a Hebrew and the air will become frigid between them. Bram is fucked by a man who afterward casually makes a joke about hanging Jews, and Bram feels lucky his parents did not have him circumcised. When others at the lab are given raises, his salary remains flat. His Gentile friends tell him he’s getting worried over nothing, but he senses that the world is back on the path to destruction, just as he’d imagined as a child.

On 30 January, 1933, an orator with a Chaplin mustache — a former Viennese, as it turns out — is given the key to the German Republic next door. Bram and his colleagues crowd around a radio in the laboratory and when Bram hears the news, he passes out and the back of his head slams against cold concrete. His few remaining professional friends attempt to revive him and, after about a minute, he returns to consciousness. He sits bolt upright and demands paper and a pen. He starts to write about what he saw.

In Bram’s vision, all of time had been transformed into to a sphere the size of a football and he was able to look at it from the outside. He was orbiting this sphere, and was indeed alarmingly large in comparison to it. He tried to raise his arm, but as he did so, the void around him exploded into colors that traced the outline of his movement and spread outward like a tidal force. He tried his legs and his head; the same thing happened. He could sense, somehow, that every time he did anything, he changed the contents of time. Abruptly, Bram felt as though a bullet had risen up to the back of his brain, causing a headache unlike anything he’d ever felt. The colors in the void turned sheer white, something so bright it burned his eyes even while they were closed. He gripped his skull in pain and a voice started speaking to him in alien syllables that he could nonetheless understand. Somehow, he knew the voice came not from a body, but rather from a name. He couldn’t understand what that meant, but he was certain of it. The name spoke.

Said the name: Avraham.

Bram choked out the words, My name is Bram.

Said the name: That was your name. I have given you your father’s name.

Bram whispered, My father’s name is Benjamin.

Said the name: Your father Avraham. The father of your nation. As he was Avram until I gave him the instructions for the covenant, so too were you until this day. And now, I give you your instruction.

Bram was weeping in agony by now. He would do anything to make it stop. Just tell me what to do, he said.

Said the name: The end of days is at hand. Clear the path for Moshiach. Speed the triumph of the son of the line of David.

For some reason, Bram knew exactly what this strange phraseology meant. He surprised himself by asking, teeth gritted, What can I do?

Said the name: The world is more dangerous than it was when I spoke to the last prophet. Moshiach must now be stronger than the strongest man.

Where will I find Moshiach, Bram asked.

Said the name: In Jerusalem, my holy city. You have your charge. Move yourself.

Bram sets down his pen. He thinks about how much it would cost to sail to Palestine. He thinks about how much money he has in the bank. He thinks about his mother. He thinks about how he likely cannot bring both her and himself. He interrupts his calculations by wondering how he understood any of what he just wrote down. He had never studied the Bible. Had he overheard these terms somehow? Had he read about them in a book somewhere? Perhaps. Or perhaps it was something else. Bram rushes home, despite the protestations of his baffled coworkers that he go to a hospital. He arrives and shakes his mother from a nap. He tells her he’s had an experience he can’t account for, in which he thinks God spoke to him and told him to hasten the coming of the Messiah. He tells her his name is now Avraham. He tells her he must go to Jerusalem and cannot take her but will arrange for the finest care for her, which will not need to be for long because the Messianic Age is upon us.

Bram’s mother, usually frail, stands up like a cannon firing and grabs her son by his shoulders. She pulls him into her body tight, tighter than she has held him since she was nursing him. She whispers to him. No one can know, she says. I believe you. But if they see who you are and that you serve HaShem, they will kill you, my son. She is crying now; first in tiny gasps and then in jagging sobs. Promise me, she says. Promise me and do what HaShem has told you. He promises her.

Bram travels by train and then by steamship to Palestine, disembarking at the port of Jaffa on 8 May, 1933 and immediately making his way to an apartment near Mount Scopus. He has acquired an associate professorship at the Hebrew University and has received financial aid from the Jewish Agency. He is filled with optimism about the task ahead. The following five months are utter misery for him. He struggles with the language. He cannot stand the draining weather and the stench of the city’s refuse drives him insane. He feels intimidated and judged by all the Jewish residents he meets, whether it be due to his physical weakness or his ignorance of Jewish history and religion. He wonders about the injustices being done to Arab and Jew alike, and the stability of the British grip. He wonders what would happen if the Jews achieved their dream of a Jewish state. The cuisine gives him terrible diarrhea. He tries to figure out how he can speed the coming of Moshiach, waiting for a sign or another experience with the name. In his off-hours, he studies the Bible and the encyclopedias for hints on how to find Moshiach, but sees nothing. Some nights, out of frustration, he bangs the back of his head against Herodian stone in the Old City, hoping perhaps that the obscure holiness of the rock will pierce the word of God into his brain. On 28 October 1933, two things happen to Bram. First, he receives a letter informing him that his mother has died. Second, riots break out and he is forced to barricade himself up in his apartment while foreign epithets are flung like shit and fires rage. The next day, he buys a ticket to return to Vienna.

Bram, after some debate with himself, concludes that his mother would prefer her Jewishness to remain invisible, even in death, and thus has her cremated without ceremony. He immediately regrets the decision, but has bigger problems to confront. Things have gotten exponentially worse in Germany, and Austria is little better. There are even those who call for the two countries to unite. Bram does not know what to do. He tried to follow the name’s instruction and go to Jerusalem, but he had failed there. His funds are dwindling and he has no job. He writes a letter to a former colleague who left a few years prior for a professorship in the United States, asking what the prospects are for his emigration. Perhaps the Americans are right; perhaps it is the New Jerusalem. He is in desperation.

Bram’s former colleague writes back to say he knows of a low-level research job in New Jersey. It involves using chemical compounds to alter the metabolisms of rats. Bram writes back eagerly to say he will take it at any cost. Before it is even offered to him, Bram decides to travel to New Jersey. Things are getting worse and worse in Europe. As the train leaves Wien Hauptbahnhof, he whispers goodbye to the city, hoping it won’t be a final farewell. In the port of New York, immigration authorities ask him his given name. Something compels him to say it’s Avraham. They write down Abraham. He says his surname is Eskin. They bastardize that one, too, into Erskine. He accepts this new moniker without complaint.

Luckily, Bram gets the job in New Jersey and starts working at a laboratory in Hoboken. He had learned just enough English in school that he gains a foothold, and a burly refugee German Jew at the lab named Walter helps translate for him when necessary. Bram keeps a low profile, but earns a steady income. He starts to worry that he is losing sight of his divine mission. He takes to cutting himself again. Then, something happens. While working late at night at the lab, alone — he often did this because he had no interest in a social life, not even a sexual one, anymore — he makes a mistake and mixes two liquids that he shouldn’t have. Unwittingly, he administers the resulting fluid to a rat. The rat suddenly does something Bram can only describe as blooming. Its musculature starts to swell and soon the rat looks like a miniature horse, all sinew and strength. Bram stares in shock. After a few seconds, the rat coughs intensely and dies. Bram lifts it into his hands and suddenly realizes how he can serve the name.

For years, Bram lives in solitude, devoting all of his off-hours to altering and developing the inadvertent serum he’d created that night. His coworkers know nothing about him, much less his project, which he works on after everyone else has left. He toils and the rats he purchases suffer as he attempts to stabilize the compound and allow the creatures to reach physical perfection. He feels an ever-increasing urgency whenever he picks up a newspaper or hears a radio broadcast. The Viennese orator seems to have the world wrapped around his finger. On 12 March 1938, two things happen. First, Bram vomits after he hears on the office radio that German troops have been welcomed into Austria for annexation. Second, while working that night in a daze, he inadvertently forgets to check to make sure he’s alone before he begins his work on the serum. Walter walks in on him and a rat in mid-transformation. Walter gasps and drops a beaker, leading Bram to turn his head in horror. Bram is about to explain using an excuse he’d devised years before as a backup, but Walter preempts him with speech. Bram, I need you to meet someone, Walter says. Meet me at the train station at 6:30pm tomorrow. Trust me or I tell everyone what I just saw. Terrified, Bram agrees.

They meet at the appointed time and place and take the train into New York City, which Bram has rarely visited. By the time they approach the great metropolis, it’s after dark and the lights of Manhattan are glittering like fairies. They take the subway to the Flatiron Building and walk to a nondescript metal door, which Walter knocks seven times. A mechanical stirring emanates upward, then the door swings open to reveal sliding elevator doors. Bram and Walter enter the carriage, the operator swings a lever, and they’re moving down, down, down, farther than Bram can account for. They reach a stop and the elevator doors slide open to reveal an enormous, bustling laboratory full of men in white coats and other men in military uniforms. Bram is staring around the room when Walter grabs him by the arm. Bram is surprised by the frisson that this sensation sends through him, but has no time to dwell on it, as they’re already walking up to one of the military types, a slightly fat and leather-faced man with many medals on his chest. Walter tells the man about what he saw Bram working on. The man’s eyes widen ever so slightly and he calls them into an office. As Walter closes the door, the man sits down at a desk and pops chewing gum into his mouth. My name is General James Gregorian, he says. Welcome to Project Rebirth. The general proceeds to explain that he and his cohort, including Walter, are working on an attempt to create a new kind of soldier, one prepared for a war. Should, God forbid, we be dragged into one, we have to be ready, the general says, his gum stretching. We need someone stronger than the biggest guy on the battlefield. Though Bram’s face remains impassive, he notes those familiar words and realizes this could be his chance. He says he will work for them. The general tells him he starts tomorrow and will be sleeping in a bunker. When can I get my possessions, Bram asks. As of now, you have no possessions, the general says. To the rest of the world, you have disappeared. Your life as it was is now over. I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news. Bram, having nothing much to lose anyway, says that’s fine and is escorted to his bunker.

For the next two and a half years, Bram completely devotes himself to his work. He accelerates through bigger and more intelligent animals with every passing month. The time comes in late 1940, when war has already begun but the United States is still uninvolved, when the project is ready for human subjects. There are 16 candidates, all soldier volunteers who defy the popular winds of pacifism and want to see the blood of their enemies spilled. Bram is on the panel that decides whether or not a subject is fit, ostensibly so he can say whether their blood tests look germane. However, he abuses that privilege and lies about unfit plasma because each boy terrifies him more than the last. Surely, none of these men are Moshiach, he thinks, and if they are to gain his power, then all is lost. One by one, he vetoes the first 15 candidates. He is panicking — if he doesn’t pick this last one, the project will be set back years while new ones are sought. But he cannot bring himself to potentially grant these abilities to the wrong person. He cuts himself again, out of anxiety and confusion. He cries that night in the bunker and begs the name to tell him what to do. He receives no answer.

The 16th candidate appears before the panel. He’s a wisp of a thing. The scientists look at one another, knowing they’ve reached the bottom of the barrel of volunteers. They ask for the soldier’s name. Rogers, he says. Stephen. They ask for his identifying information: numbers and codes, which he provides. They ask for his next of kin. My mother, Anna Moskowitz, the boy says. She lives in Brownsville. Bram’s ears perk up. They ask why he has chosen to volunteer for the program. The boy pauses. He says he knows a war is coming. He says he has a duty to protect the weak at any cost. He says he would do anything to save the idea of freedom, and so on and so forth. He says his mother’s family is still over there. Bram is moved, but unsure. He knows not to be seduced by charisma. However, his uncertainty is outweighed by necessity and he tosses his sole shreds of optimism on the fire of the young man’s passion. He marks the candidate as acceptable for a test.

The night before the serum is to be administered, two things happen to Bram. One is that he makes a last-minute tweak to the serum and forgets to write down what he changed. The other is that he goes to the bunker to speak to the boy. They exchange pleasantries for a moment, and then Bram asks him a question. Why did you really volunteer, he says. I won’t tell the others. Well, the wisp says, I guess it’s ‘cause I’m scared. I swear, I spend every single day terrified of what might happen if the bad ideas beat out the good ones. The only way the fear goes away is if I think about what a perfect world could look like. And what if we fail and you die, Bram asks. Knowing I tried is enough, the boy says. Silence. Bram nods his head and walks back to his room.

On the day of the test, the military men and the men in the white coats gather around a medical table, crammed into a room too small for the crowd. The boy lies on the elevated surface, prepped for injection. Bram holds the syringe and looks into the boy’s eyes. He wonders if this is Moshiach, this beautiful, Jewish boy. He wonders if the boy will be able to stop the march to oblivion. He wonders if he was able to aid the boy sufficiently in his possible path to the throne of David. He closes his eyes and searches for a prayer to say, unsure how the words will sound coming out of his lips, when Walter, behind him, starts whispering the shehecheyanu: Blessed are you, Lord our God, king of the universe, who has kept us alive, sustained us, and brought us to this season. That’s good enough for Bram. He pushes the syringe. The serum enters the boy. The boy starts to bloom.

A commotion. Bram turns his head and sees a man pushing his way through the crowd. The man comes to the front and fires at the boy. He misses, but the bullet starts ricocheting around the metal walls. Suddenly, that pain: a bullet in the back of his brain, this time quite literally. The void and the screaming white. The name speaks.

Says the name: I will give you your life in a grain of sand.

How will I see something so small? Bram asks.

Says the name: Is it not enough to know it is there?